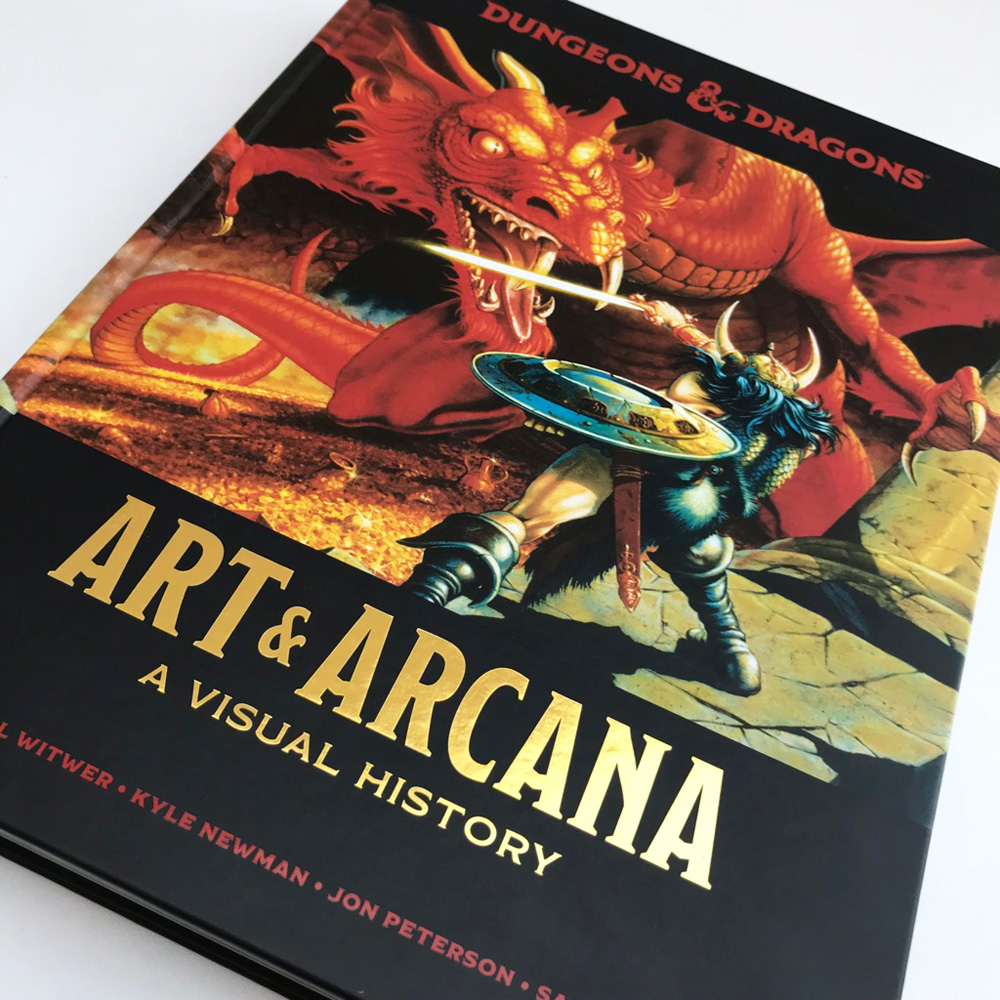

The recent publication of Arts & Arcana – a visual history of Dungeons & Dragons – takes my mind back to the 1980s and playing D&D every weekend with my grade-school friends.

The artwork in those old books and modules, and the novels that sometimes accompanied them, has always stuck with me. In 2010, I was lucky enough to get a commission from ImagineFX magazine to write a cover feature about the art of Dungeons & Dragons and I delved back into it. I thought now, with the arrival of an official account of the game’s artwork, would be a good time to share an interview I did with Larry Elmore. The Kentucky-based artist painted the image that probably represents the game better than any other – the barbarian attacking a red dragon, which featured on the Basic Rules box.

Let’s step back to August 2010, when I spoke to Larry on the phone…

Wizards of the Coast has just brought out a red D&D box set for beginners, which goes back to the 80s and the Basic Rules box with your painting on it. It kind of marries the old tradition that you’re part of with some of the newer stuff. What are your thoughts on it?

Well, I think it’s good. I know when I was doing the box covers – me, Caldwell, Easley and Parkinson were working there at TSR – we were setting a look for games. We were just sort of painting the way we wanted to and there wasn’t much fantasy art around at the time, so we didn’t have a lot to build on. Frazetta of course, and a handful of artists.

We were just doing our thing, and of course we played D&D so we knew that the weather and everything in the scene was important to the game, the time of day, you name it, if you were a gamer. So it’s very neat to see it evolve now to the look it has today. I talk to some of these younger artists and they say, ‘We sort of had you guys to stand on your shoulders and to keep going, and keep changing it.’

It’s very exciting to see what they’ve done. We thought we were bold and exciting but they’re doing a lot more now!

Are there any artists whose work you think is outstanding at the moment?

As far as a painter, I really like Donato Giancolo. I think he got his start doing card art for Magic: The Gathering. I just think he’s a great painter. He paints like an old master. There’s Matt Stawicki who also does a lot of art.

An English guy did the images on the manuals that are inside the red box, his name’s Ralph Horsley.

I’ve seen that, it’s very good.

I was talking to him the other day and he had a lot of good things to say about you and how you influenced him.

Well I think it’s like a big circle. We might have influenced those young guys, but now you look at some of the stuff they do and it influences me.

Before you joined TSR there were guys like David Sutherland III and Erol Otis – how much did they influence you? People today might see their stuff and say that it looks quite primitive or perhaps it didn’t feel branded, whereas you developed it into a look.

When I went to work at TSR, I was the first person who’d done very much work professionally and had been published. I’d been an illustrator for eight years before I went to work for them. After the Army I became an illustrator. I’d been published in a few magazines. David Sutherland and some of these guys, I don’t know if they’d had any classes or lessons in art. Sutherland, I don’t think he had, but TSR was young and they needed art and they said, ‘Do you know how to draw or paint?’ and then someone would say ‘I do a little bit,’ and then someone would say, ‘I’ve got a cousin who does a bit.’

I think when they hired Erol Otis and some of those guys they were young, very young, and they were just getting out of school and just starting. I would say they were in their early 20s and when I went to work there I was already 32 or something like that and Caldwell and Easley were about my age too. So we were 10 or 12 years older than some of the guys who were there first, but they weren’t there that long, only a very short time before we came in. Then we were there long enough to develop the look.

What do you remember about that period – what was the atmosphere like?

It was wonderful, it was the most creative place that I ever worked at. I know it changed later. We worked together in one big room and there were the writers, artists and game designers and we shared ideas and played games together and created together. It was just a magical place to work at that time. Everyone got along. Everyone was happy to be there, knew we were lucky, but there were always management problems. People fighting for control of the company. There was always some big battle and sometimes we didn’t know what was going to happen, if we’d have a job next week or what. That was a downside. But the plus side was we loved it and we all had fun, worked together – it was magical. Things like that happen only maybe once in a lifetime. You run across a place where everyone gets together, gets along well and you can work together – it’s just rare.

When you think back on all the Dungeons & Dragons artwork that you created, which are your three favourite pieces, or the three pieces that you feel are still important?

Well, I’d say the old red box cover. That was seen a lot and I didn’t think much about it at the time but it really had an impact on a lot of people. And then there’s the first Dragonlance painting that I did. It was a calendar cover and was used on a few things. That piece, and maybe the first Chronicles cover, Dragons of the Autumn Twilight, because we were really excited about the project and we really wanted it to be successful. It was the first project that came from the creative people, and not necessarily Gary Gygax. It seemed like at that time he had control of everything and if something wasn’t written in his world or his domain, it wasn’t published. So here comes Dragonlance, it’s totally another world, another situation, another story. And it had a story, it wasn’t just a gaming world.

We wanted it to be successful and we had a lot of energy and we put everything into that, and it did really well.

I loved those images. I think I was 13 or so when Dragonlance came out.

On Dungeons & Dragons, I liked doing all three of the first three box covers. I did a lot of module covers and some of their Endless Quest or Pick-a-Path books. Hmmm. They all sort of blur into one.

I did a lot of Dragon magazine covers which I liked because they’d give you a lot of freedom.

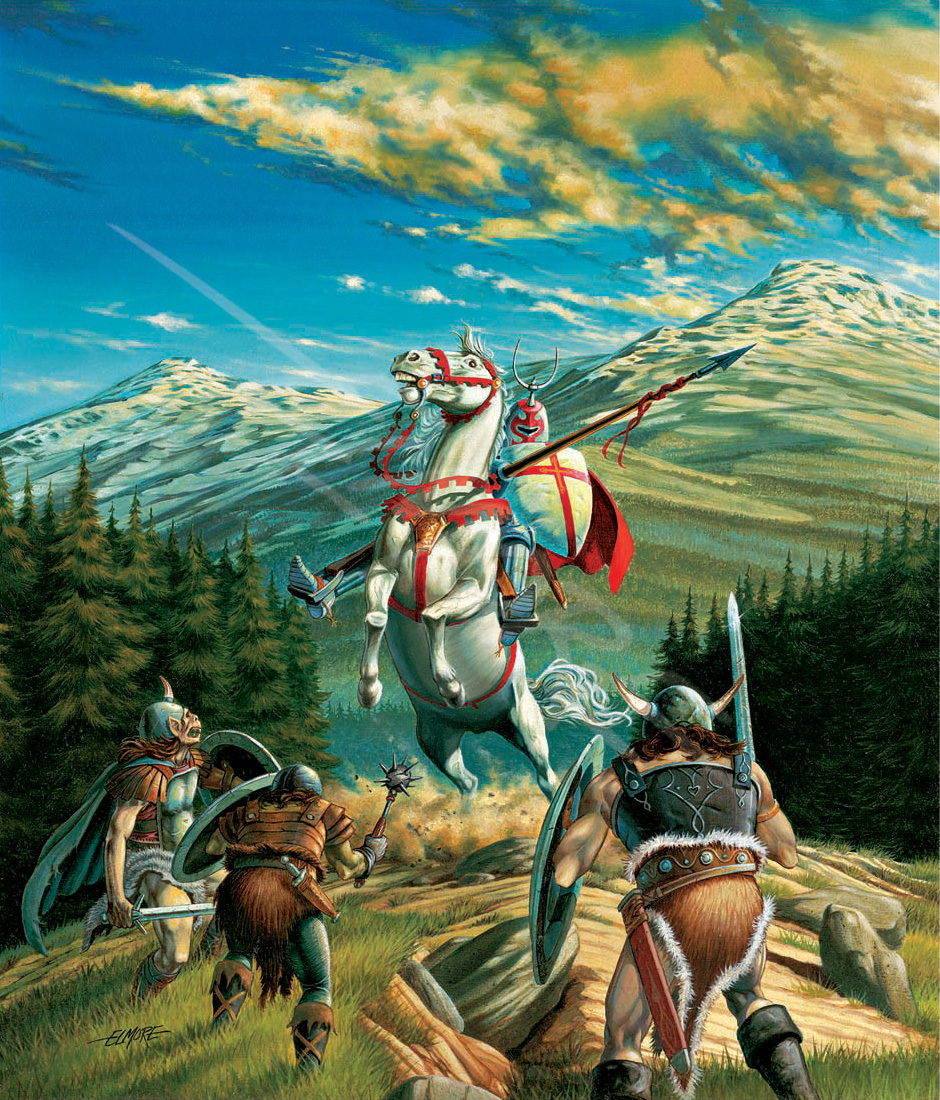

Did you do one where there’s a guy on a horse and it’s rearing up and there are some orcs in the foreground?

Yes. That was the first Dragon cover that I ever did. I think it was 81. That’s the first year I worked there.

Was Dragon magazine separate, or was it something you had to do in the same way as you did the D&D stuff for TSR?

Dragon magazine was a part of TSR but the neat thing was you could do a cover for that in your own time and get paid for it. And the other thing was they tended to give you a lot more freedom than doing a cover for a game or a module or something like that. I loved doing Dragon covers, mainly because of the freedom that I got. Sometimes it was just a subject matter, like ‘magic weapons’. I could do a painting of just about anything I wanted to fit that.

A lot of what we did back then was module covers. A module was written so it was almost like doing a book cover. You would have to read through and see what the setting was like so that you could illustrate true to the module.

Was there every a situation where you played the game, imagined something and then that was in the painting?

Yes, I’m sure there was. Playing the game made you realise how important everything around you was. The landscape or the building – everything was important. The dangers that lurked around. All these things filtered into those of us that played it and came out in the art in some way.

At that time TSR was such a popular company, and it was growing fast and making a lot of money. A lot of advertising companies would approach us to get their illustrators to do art for us, and they would send us samples by the illustrators that they had in their stable, and it was great art, it looked like advertising art, it was probably better art than what we were doing at the time. We were like in our early 30s and these were guys in their 40s and 50s, but it missed something. These guys didn’t play D&D and didn’t really understand it, you know.

So the art was slick and perfect but it didn’t reflect the game somehow. Playing the game and loving what we did, we were into fantasy worlds, we were consumers of fantasy products. Our art was different than a normal illustrator who had never played games like that or read a fantasy novel. They just weren’t into it. So you could see a big difference.

How would you characterise the difference?

One thing – we were putting our heart into it more than anything. We were young, we were learning, we were still learning how to paint too. We’d all been to a school of some type and were educated in art but it takes a while to really become a painter. The fantasy influenced us so much. Most of us had read a lot of fantasy. The artists had a distinct look. I think there was more attention paid to the sky, the ground, the landscape, everything, even the threat when we painted a monster.

I didn’t paint many monsters but Jeff Easley was great at painting monsters and we influenced each other. And of course, like I said, Frazetta, the Hildebrandts, Jeff Jones, a lot of artists from the 60s and early 70s. Michael Whelan. He was painting then, and some of those guys influenced us too and they were into fantasy. Fantasy was expanding and then there was us doing the D&D stuff and we were I guess influencing other artists, though we didn’t know it. I think all the fantasy artists at the time were influencing each other.

We were coming from different directions in fantasy. Some were reading it and that was it. We were coming from gaming and so I think we all had an impact on each other. And then you had different role playing companies hiring different artists, trying to compete with each other. It was really quite a movement I’d say.

With the gaming artwork, you’re giving players a visual clue. Looking at the picture on the front of a module or the cover of a novel sets off your imagination and that becomes the basis for how you see the gaming world. Is that how you see it?

We played almost every day. We had one campaign that ran years. We’d play every lunch and then once a month we’d go to somebody’s house and play all night. And when we painted characters, like when we’d paint a wizard, we knew, we’d give him packs, we’d give him pouches, we’d give him scrolls because we knew that playing a wizard you had all this stuff.

In the game you carried a lot more stuff than you could probably carry in reality, but that was accepted, you know. Like when we did an adventurer, he would usually have pouches and if we had to we’d show a backpack. We’d put ropes and little pouches and maybe a hook or something to climb walls. And a fighter, we gave him armour that looked functional most of the time – really functional armour.

We were also influenced by the SCA – the Society for Creative Anachronism. It’s people that dress up and fight. We’d run into these guys at conventions and they were all armoured up and they’d fight each other and you’d learn from them too. What’s the more functional armour. We did the whole thing according to how, if the games could come to life, the characters might be.

Today you look at a lot of fantasy art and the armour is not functional, it would get you killed. It’s just impractical. The weapons are way oversized, which you couldn’t even wield. People aren’t carrying anything. It’s just carried itself to another level. I think the art is more dynamic but it’s not as realistic or functional as it would be in a game.

The old red dragon. When I painted that, well a barbarian type guy was the only guy that didn’t carry a lot of stuff in the game. So I had just a simple barbarian fighting a red dragon and you can’t even see his face. I made it very simple. It was the basic game.

Do you still play?

No, I can’t, I don’t have time.

When you look back now how important was painting Dungeons & Dragons full time to your career?

Well, it made my career. I was working, I was doing fantasy, and then I went and worked for them, and we all loved it.

I remember one day when Clyde Caldwell and I got into an argument. We were all sitting in a room there working, and Clyde or someone said, ‘What makes an artist really famous? What really puts him on the map?’ That was the question, and I argued that if he does good work, if people like his work, he will become popular.

Clyde Caldwell said if you did a great book series or something really popular that becomes a bestseller, that would put you on the map. It doesn’t make any difference how great your art is. That would do it. And so we argued over that for probably 30 minutes.

One thing from that argument I do remember is that at the time I was painting the first Dragonlance painting ever done, and Clyde was right. I did the covers for Dragonlance – the first 11 covers – and that series of books did more for me than anything else I did.

So I had two things going. I did the old Basic, Expert and Companion boxes and I did the first covers of the Dragonlance novels, so I had a double lucky hit and yeah, God, I appreciate it. I was glad that it happened, because I’m an OK artist, I’m not great or anything, there’s a lot of people who are better than me out there. There are so many different types of art and artist and people have different tastes so it’s hard to say one artist stands out more than others but to make it through their whole career an artist has to really work hard and do good work and be lucky at the same time.

These days you’ve got these things like World of Warcraft where the game serves up graphics all the way through. It’s no longer being played in people’s minds. What are your thoughts on how today’s D&D artists are working in a different context to yourself?

So much has changed in the last 15 years it’s just unreal. I never dreamed it would change this drastically, and there’s so much competition. The fantasy field, the fantasy industry as a whole, has exploded. So you’ve got artists trying to survive, trying to make a living. That’s one thing people don’t see. Behind the scenes the artist might be married, have children, house payments, car payments, insurance, and they have to make as much money as they can and that is the curse. When we get together and talk our biggest complaint is about making a living. If we didn’t have to paint for money and could paint for ourselves, there would be so much greater art. If you’re single and you don’t have any obligations, you can do more of your own thing, but this is survival. It’s hard.

And now gaming is taking that one step farther. It’s not in your imagination, it’s on a computer and you can almost live it, and there’s something to be said about that compared to using your imagination. But the artist, there’s so much art and they’ve taken everything up a notch, with the aid of computers. Even traditional painters, the computer is still influencing them because there are things being done there and they’re being done so quickly, so many designs, it’s unbelievable, which inspires artists and their paintings.

Going back to games being played on a computer and games being played in your imagination – on a computer game you can play it a lot and you can remember it, and it does have an impact, but when you play a nice D&D campaign with everything in your imagination, you remember it the rest of your life. It sticks to you. It’s more real than a computer game. You’re there one-on-one with the people you’re playing with. The work that goes into a role playing game, the enjoyment that goes into a role playing game, what you get from it sticks in your imagination forever.

I don’t know why that is. That’s my explanation, the best I can come up with, but there’s a difference. A role playing game, played with friends, has much more impact is much more fun than online.

What was Gary Gygax like to work with?

He quickly became like a god to the people that worked there. I think I was 32 or 33 when I went to work there and Jeff and Clyde, they were about my age. Keith Parkinson was the baby of the group. He got hired in at about 21, but we saw a lot of potential in him. But Gary was an older guy and all these kids looked up to him. Well, I had been in the Army, and I’d worked in the civil service for about eight years when I got out of the Army. Being in the army or in the government working, there’s a lot of rules and regulations. But working at a public place like TSR, a regular company, I didn’t understand this attitude they had towards Gary. To me he was just the boss and the most he could do to you was fire you, right? He couldn’t put you in jail or anything for disobeying a rule. He stayed invisible a lot. He was in his office mainly. Some of the people would come up to you and say, ‘I saw Gary today.’

‘Well, big deal, he’s just a guy.’

And so I remember when I was doing the old red box cover, they said Gary wanted input on it. He wanted it simple and with a lot of impact. I’d done some sketches. At that time we did have an art director and I gave them to him and he went to see Gary and he came back he said, ‘He didn’t like these, he wanted something else.’

He was trying to tell me, and I said, ‘Why can’t I talk to Gary, he’s just down the hall?’

He said, ‘I don’t think you can.’

I said, ‘Crap!’

I just grabbed some paper and pencil so I could take notes. There was this big office where his secretary worked and his office was behind hers. So when I went in I said, ‘I want to see Gary.’

And she said, ‘Do you an appointment?’

And I’m like, ‘No, I want to talk to him, I’ve got a question to ask.’

The door was open a bit, and I could see him inside, probably just sitting there doing nothing. I said, ‘I’ve got to do the cover of this Basic D&D, it’s important, I need to talk to him.’

And she was giving me the runaround and finally Gary got up and stuck his head out the door, and he said, ‘You wanted to see me?’

I said, ‘Yeah.’

And he said, ‘Well come on in.’

So I went in and we discussed it, and I did some sketches, and I understood what he wanted. I thought it was a good idea, what he wanted. He wanted it to jump out at you, and I’d been doing some stuff for the Army two years before that where we had tanks bursting out of a frame, like bursting out of the page, trying to get more impact. So I said, ‘I know what you’re talking about.’

So from that point on Gary and I had a good relationship and anytime I wanted to see him, I’d go in and see him. My attitude was he’s just a guy, he’s just designing games, and if he doesn’t like me he can fire me. Other than that, why can’t we get along? We’d just talk. And we did. We had a good relationship and respect for each other until he died. And I was lucky I got to talk to him the year before he died, actually a few months.

Gary was a good guy at heart and he tried. He was doing the best he could. He wasn’t the best designer in the world or the best writer in the world but he did his best, as all of us were doing. I don’t think any of us were the greatest but we all worked together as a team as much as possible.

I’ve asked all my questions. Is there anything you want to add?

One thing. When all of us were working there, especially the artists, we were sitting in one big room, and we were painting and not saying much, then someone would look up and say, ‘You know, we’re really, really lucky to be here.’

And we’d all agree because we knew we were working in a hot gaming company and we knew it was different, and we knew that just about every intelligent young kid in America was playing the game. We got letters every day at TSR and they posted them on a big bulletin board, and you’d read these letters and you knew that we were having an impact. We knew we were lucky because every kid in every letter said they wanted to grow up and work at TSR. But then as it went on, after about seven or eight years the fighting and the struggle over the company got so bad the whole atmosphere changed. I was the first artist to leave out of that group, and then Keith followed me, and then they hired some more in.

I went up there and visited them a few times in the 90s and the whole atmosphere was different. It wasn’t the same company anymore. That fire, that thrill, it had gone out. Some of the individual artists had that feeling, but the company as a whole, it changed attitudes, it wasn’t a fun place.

I can say that working there was the most unique and best place that I ever worked in my life, and it was about eight years of nothing but fun. You’d go into work and you’d work there til nine or ten at night sometimes. You didn’t want to leave, you just kept working.

I still need to paint. They’ll have to prise the paintbrush out of my cold, dead hand before I’ll stop.